“I was just aged 20 when my dad had a stroke that left him with significant mobility, speech and cognitive issues. Actually, when we suspected dad may have had a stroke and took him to hospital, he walked onto the ward completely independent. Yet, by the time he left hospital after four months he was completely bedbound. I can still recall the consultant planning dad’s discharge saying the words ‘vegetative state’ and ‘needing around the clock care.’

“We were left with two options for dad’s care, either we would have to think about a nursing home, or we would have to provide that 24-hour care for him at home. At home was my mum, who had her own health issues with debilitating rheumatoid arthritis that would leave her bed bound for days. She had been poorly with her arthritis many years and long before dad had the stroke. Also at home was Sam, my older sister. At that time both of us were working in the NHS. Between us we came to the decision that there was no question that we wanted dad to come home.

“Before dad was discharged an Occupational Therapist visited us at home to carry out an assessment. We initially got a bed for him downstairs, and then other equipment followed in the weeks and months on. They wouldn’t provide us with a hoist as they didn’t think we’d have been confident enough to use it, but I think it would’ve been really helpful, especially with the amount of lifting that’s involved when caring for someone with complex care needs. With appropriate training, I’m sure we would have picked it up. Looking back on it now, being so young and having no experience engaging with health professionals, I just assumed they knew best. Back then I had no idea around how to make complaints or had an awareness around carers’ rights. I think if that assessment had been done today, I’d have definitely challenged a lot of the decisions that were made.

“We also were provided with an enablement care package when dad came home from the hospital, but only for a period of six weeks, where carers would visit us at home to help dad. But there was such a lack of continuity with this care. We’d have different carers come to visit him and there was no set time or structure. Also, the calls were set up at unhelpful times, for example we’d get our morning visit around 10am, but obviously we couldn’t leave dad in bed waiting for the carers to arrive. Also, it would have a knock-on effect with a late breakfast conflicting with the lunchtime call, meaning often enough the carers would end up leaving no sooner than they had arrived – because there was nothing for them to do.

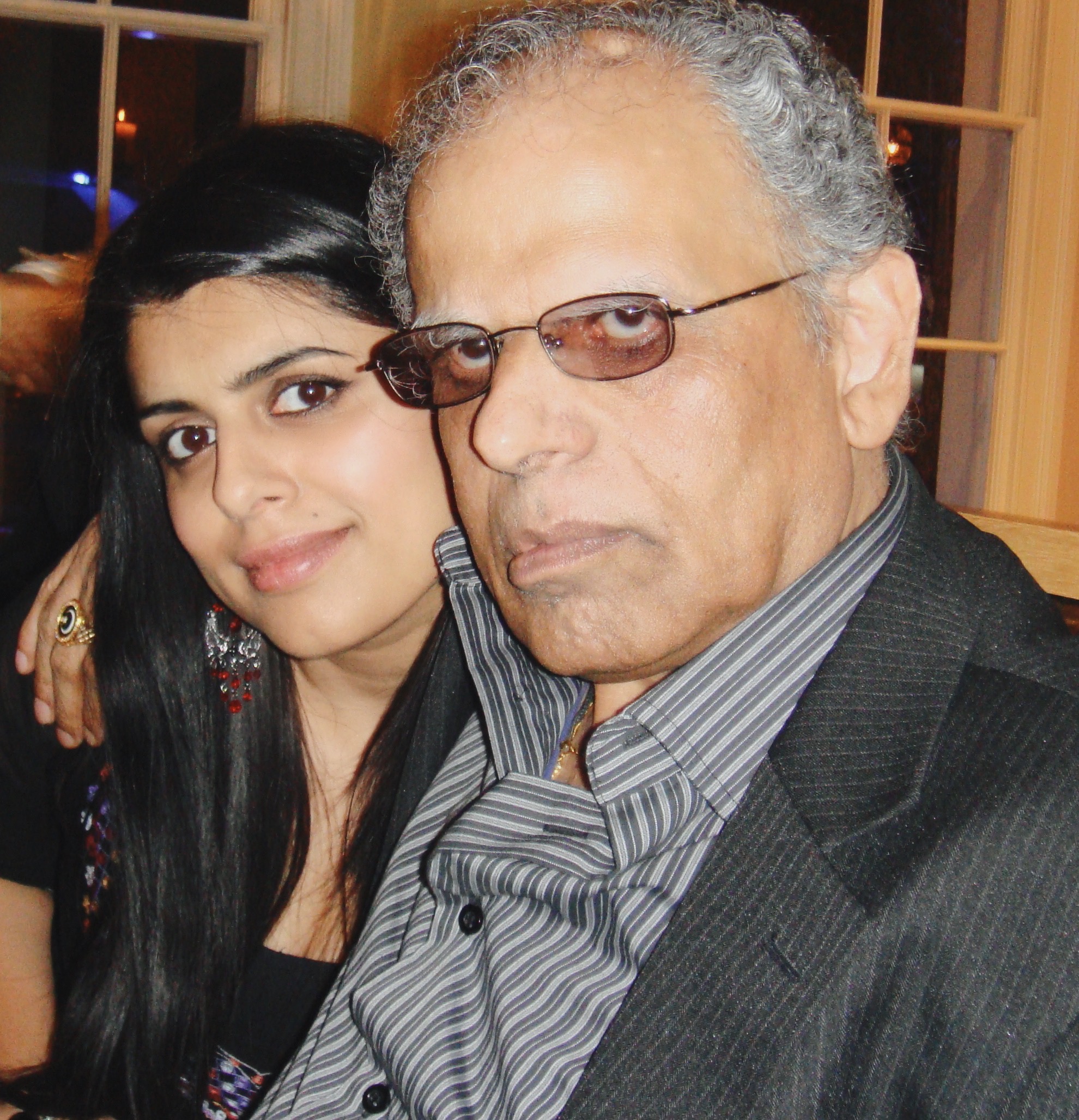

“It was really important for us to have carers who would take an interest and get to know dad and not just his care needs, particularly given that dad was non-verbal at that time, just being able to pick up whether he was having a bad day or wasn’t feeling well and so on. It was important for me that carers visiting looked beyond his disability and got to know him – his love for comedy classics, any opportunity to embarrass us with his impromptu ‘dad dance’, and his passion for fashion (and some crimes against fashion too).

“Dad wasn’t really able to communicate with us in any way during those early days following his hospital discharge. It was like he was trapped inside himself. He could hear us, he was listening, but he couldn’t communicate. I recall one evening being perched on the side of his bed and watched as tears began streaming down the side of his face. I can’t even begin to imagine the frustration he was feeling. I remember how hard I had to fight for speech and language therapy and physiotherapy. The clinicians were reluctant to offer dad rehabilitation services as they tried to reason with me, they didn’t know how much more of an improvement these interventions would bring, and what that would add to his quality of life. But I had to really challenge what their definition of quality of life was. How would they measure that? At that time, I didn’t think dad was going to be able to get out of bed let alone going back to who he was before the stroke. Yet if he could somehow communicate with us, either through blinking or even managing to say a word, that would definitely be an improvement. Even if it was a tiny progress.

“Not only did I put my efforts into caring for dad, but into ensuring he was getting all the support he needed. At the same time, I was learning to navigate the maze that is the health and social care sector. I remember speaking to a lovely lady from the Stroke Association who was a godsend. She gave us invaluable information around applying disability support for dad, equipment and community services to help with his daily care and carer groups we could access and meet other carers to offload and recharge. It was around that time I kept being referred to as a ‘carer’.

“Having fought so hard for dad’s speech and language therapy and physiotherapy, I made sure that we continued to do his exercises between appointments as he had aphasia, resulting from the stroke, effecting his ability to form sentences and leaving him struggling to communicate.

“The hard work and pushing for rehabilitation therapies were paying off as speech and language and physiotherapy were having a noticeable impact. In fact, around six months after dad’s discharge, he reached a stage where he was able to manage his own personal care, brush his teeth, comb his hair and even feed himself.

“With support he was able to take some steps and then progressed to walking without any support or aids. So, when dad met with his consultant just six months later, the same consultant describing dad’s state as ‘vegetative’, and walked into the consulting room, the expression on the consultants’ face was memorable to say the least.

“I remember feeling an overwhelming sense of pride – for all the effort he’d put in and his perseverance – that’s my dad. He always was quite a stubborn sod and I think that really worked to his advantage. He never gave up. Although, I felt the health professionals did give up hope on dad making any recovery from the stroke. Hence, why we were asked if we wanted him to go to a nursing home.

“After dad’s initial stroke, he became prone to experience Transient Ischaemic Attacks, or mini strokes as they are commonly known. He continued to make progress but after many TIAs it was beginning to feel like it was one step forward and two steps back. At the height of dad’s increased care needs, I reduced my working hours and then had to leave work altogether. It was becoming difficult for mum to balance dad’s care alongside her own health issues. There were periods when dad’s care needs were stable and I managed to get back into work. But it was never for long. The fluctuation in dad’s health and the unpredictability around his care needs made it really difficult to hold down a job or make plans.

“Before dad had his stroke, I had plans to go to university, but I knew caring for dad had to be my priority, so I decided to apply the following year. Consequently, a year ended up turning into 10 years when I finally did manage to enter higher education – I was what they call a ‘mature student.’

“At the time there was a perception amongst professionals within health and social care that because you belong to a South Asian community there is a network of extended family that you can call upon for support. Which is really frustrating because we’re no different to any other family who have caring responsibilities for a loved one and any support would have been snapped up. There were times when we really struggled.

“It was great seeing dad’s improvement and how much he’d had accomplished but that came at the expense of my own physical health and emotional stress. I always felt restricted, like how much of my life is my own, because I committed most of those 14 years to looking after dad. His care needs always took priority. I think that’s carers in general. We always put ourselves right at the bottom when it comes to our own needs, and we just prioritise everything else. I think many carers will relate by the fact that even when you’re not with them, routinely you will be thinking about something concerning them – picking up their prescription, making an appointment, following up that call. We’re always on autopilot. We’re always on high alert. It’s relentless.

“Dad went into hospital for the last time in July 2014. He had been in hospital so many times over the years that I used to say in jest the hospital should have a plaque put up in his honour. It became somewhat a regular conversation the clinicians would have with us about dad being really poorly and preparing us about the possibility that he might not be coming back home. Yet a few weeks on he was back at home calling the shots. So much so, that I must admit I did become complacent.

“Dad passed away peacefully on Eid day, following the blessed month of Ramadan, with all of the family around him to say our final goodbyes. It was pneumonia in the end. He just wasn’t able to recover from it. It felt surreal that with everything he went through with his stroke and TIAs, that it was something so unexpected that would be the cause. He was just aged 64.

“I managed my grief by shifting the focus onto mum. I knew what the impact of losing dad would have on her. Although, I don’t think she was too pleased with the attention.”